Ecological Dynamics in Rehab

A woman with very acute lower back pain came to see me for an assessment. Her pain was sharp, intense, and radiated down her legs. She worked full-time and couldn’t afford to take time off, had 3 kids, and told me that she was under a lot of stress.

Her priority was to take the edge off of her pain so that she could at least function in her day-to-day life, and I agreed that getting her symptoms under control would be a good first goal. We explored some very gentle movements during that first session and found a couple that were helpful, and I did some manual therapy that she said was quite relieving. By the time she came in for her second appointment, she said she felt about halfway back to normal.

Motivated by this success, I gave her some movement progressions and continued with the manual techniques that had been helpful. She made great improvements in her mobility and strength over the next few weeks, but during our 5th appointment she mentioned that even though she was still gradually improving, she couldn’t help but feel that she was always on the verge of a flare up.

Load Tolerance

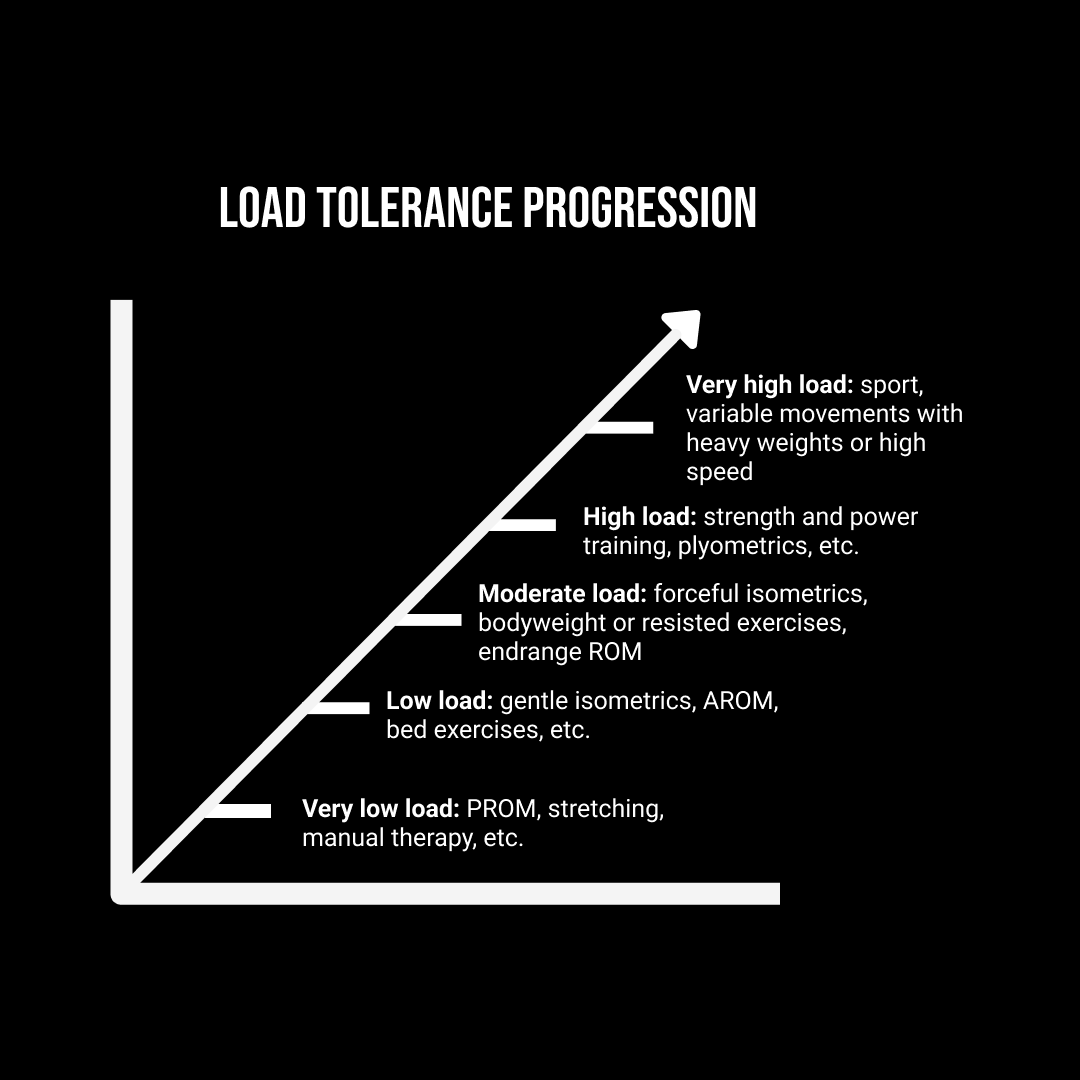

The traditional biomechanical model in physical therapy is about physical capacity and gradual load progression. The assumption is that pain is a response to a real or perceived threat, and that having a lowered physical capacity (ie. loss of strength or ROM) can create a sense of vulnerability for the nervous system. Therefore, improving those deficiencies should remove the vulnerability and resolve your pain, and in most cases, this load tolerance model works very well.

Unfortunately for this client, she was already meeting most of the classic physiotherapy checklist items, like restored range of motion and improved strength in a variety of functional movements (we had progressed her from only doing gentle bed exercises to being able to lift weights off the floor pain-free), but this did not translate to physical confidence. There seemed to be more going on.

I asked her why she felt fragile, and her demeanour suddenly became very serious. She said that she knew she was taking on too much in her life, but she couldn’t give her body the break it needed because so many people were relying on her. “What am I supposed to do?”, she asked. “Everyone in my life needs me.”

This was true in many ways. She revealed to me that her mom was sick; in addition to taking care of her kids and working as nurse, she had recently became her mother’s primary caretaker. She didn’t have a lot of family to help, so it fell on her to do many things for many people. Despite having no spare time for herself, she still made it a priority to do her home exercises because she desperately needed to be able to function for her family. The fact that she was able to attend all of her appointments and follow her home exercises regularly despite all the other demands in her life told me that she didn’t need a lesson in prioritizing her needs, nor did she need another list of exercises to work through. The reality was that even though it wouldn’t be permanent, she was going through a particularly demanding time in her life, and she needed help understanding and addressing her body’s needs in the midst of it all.

In light of the pain science literature, it’s tempting to write off the load tolerance model as outdated. After all, lots of very strong, physically capable people still struggle with pain, and there are certainly people who lack strength and mobility who don’t have much pain at all.

The funny thing is that the physical load tolerance model is not only very helpful for simple rehab, but I’d argue that we have to take it even further for complex cases. I think that looking at the load tolerance model through a biopsychosocial or ecological dynamics lens is probably the closest we can get to accurately understanding complex pain: load tolerance doesn’t just apply to withstanding physical forces, but also other personal factors, like digestive, immunological, cognitive, and emotional, as well as interpersonal and environmental elements. Too much stress in any one of these categories, or too great a sum of any combination of them, and we become more susceptible to pain.

Redirection

Acknowledging her feelings was a step in the right direction, and our conversation certainly revealed the complexity of the situation, but it was all quite overwhelming for her. Our clients sometimes share personal details that we can speak to, but as a physical therapist, it was not my place or within my scope to help her process the heavy psychological elements of her circumstances. I think that clinicians and trainers can take on a lot of emotional load in our work, but I think that being secure in what we can do well (movement, manual therapy, and education), as well as knowing how to shift those conversations to a more constructive place, is quite liberating. Not only does it prevent clients from spiralling into unproductive thought cycles during their sessions, but it also helps us be more effective as physical health professionals.

When I find myself in these kinds of situations, I like to ask my clients: “what would you like to get out of our time together today?” I find that this is a really gentle way of giving people the freedom to express their needs without straying into areas where I cannot help them, and it redirects their attention toward actionable items that are within our scope and control.

She said that what she wanted most was a way to get rid of the “fragile” feeling in her back. I asked her what that meant since she was already quite physically strong and mobile, and her pain was improving every session. She said that the thing that made her feel most fragile was the feeling of stiffness she would get while at work. Since she didn’t have space at the hospital to do her home exercises, she often went about her day worrying that her back would seize up again, just as it had before our first appointment. Showing her different versions of her home exercises would have given her a solution to that specific problem (lumbar stiffness at work), but it would not have taught her the underlying principle of how to understand her body’s signals and how she could address them with movement.

Ecological Dynamics

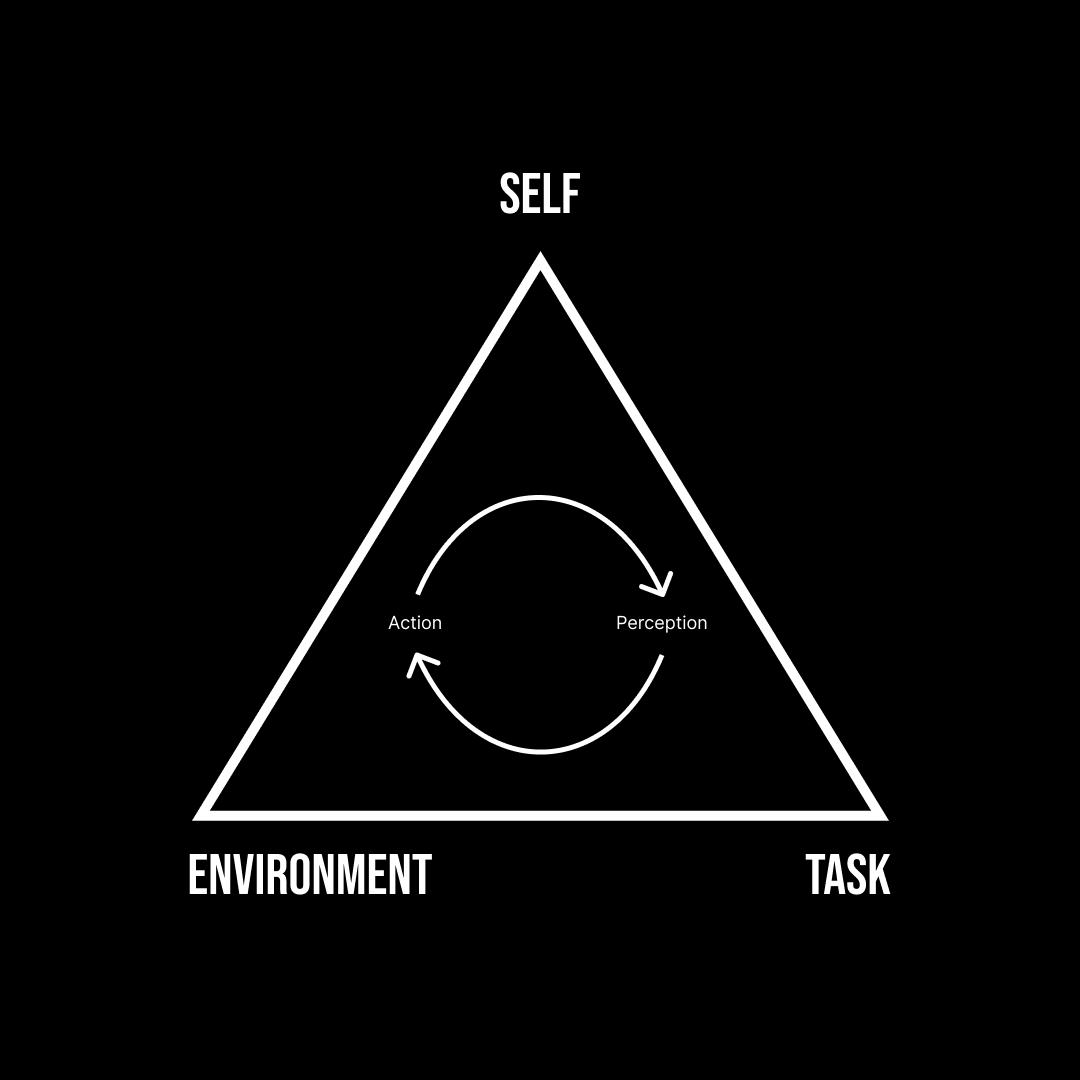

I mentioned earlier the term “ecological dynamics,” and without getting too far into its nuance and detail, I’d like to explain what it is and how it relates to my client. Ecological Dynamics is a framework that helps us understand how individuals interact with their environment and with the tasks they engage in, emphasizing that these relationships are complex and continuously changing. Through this lens, we’ve learned that experiential approaches to both cognitive and motor learning are more effective than traditional memorization and prescription-based approaches.

The way you were taught as a child was probably based on the traditional memorization and prescription-based approach, whether it was for school or in sport. Using sport as an example, the traditional model involves your coach teaching you techniques and rules so that you can recall them later when it’s time to perform. For example, your coach might have taught to pass a soccer ball with the inside of your foot for accuracy, or to shoot with your laces for power, so that during a game you could perform the “right” technique at the “right” time. The idea is that by practicing these techniques, your “muscle memory” would help you perform them whenever you decide to run that motor program.

However, as Ecological Dynamics reminds us, the individual, the task, and the environment are all inextricably linked, meaning that practicing something only makes us better at that specific thing in the context we are practicing it in. Just as practicing inside-of-the-foot passes against a wall might not help you deliver an accurate long pass while under pressure from a defender, getting stronger and more mobile hadn’t helped my client with her fear-based perceptions of vulnerability.

So, rather than teaching her another technique to practice at home, we set some “constraints” within which she could figure out which movements she could use to reassure herself. Those constraints were:

The movements should feel neutral or helpful (forget the phrase “no pain, no gain.”)

The movements should target her lower back or the areas around it, such as her ribcage, pelvis, and hips

The movements should be doable anywhere (ideally standing, with no equipment).

I asked her which of her previous exercises fulfilled all three criteria, and after some thought, she was pleased to realize that she had already learned some movements that she could use at work. She just hadn’t thought to use them because she had only ever done them at home before getting into bed. I then asked her to find one more movement, something we hadn’t done, that would also work. With some guidance, she came up with a new stretch that she felt good doing, and that ended up being the most powerful moment from all of our sessions together.

Up until then, her relief relied on my treatments and the exercises I showed her, but in that moment she was able to go through the problem-solving process herself. At her next appointment, she excitedly showed me other stretches she had come up with, and said that she was no longer as concerned about flare ups—not because they wouldn’t happen, but because she felt like she now knew how to deal with them.

Application

What I like about the Ecological Dynamics framework is that it gives us a simple way of approaching multi-faceted issues, such as complex or chronic pain. It’s not all-encompassing, but I believe that it allows us as health professionals to make full use of our scope of practice. This gives us the best chance of being able to help people that may not have seen success with more traditional forms of care.

Here’s an summary of how I used the individual-task-environment structure with my complex client:

First, identify your (or your client’s) personal constraints. What are you good at? What do you struggle with?

For my client, she had great strength and range of motion, but her primary constraint was the fear of injury that was triggered by her lumbar stiffness, so we focused on movements that could use to address that stiffness while at work.

Second, identify the task’s constraints. What types of things do you need to be able to do?

For my client, a wrist stretch would not have been very valuable: she needed a movement that could address the stiffness in her lower back, so we targeted her ribcage, lower back, pelvic, and hips.

Third, identify the environment’s constraints. What kind of equipment do you have access to? When does it make sense to practice your exercises?

For my client, having her bedtime routine was very helpful, but adding the workplace stretches was a game-changer.

It all seems very common-sense when we think in these terms, but I think that it can be difficult to integrate these kinds of things into our practice if we’re only thinking in terms of load tolerance and progression. At the end of the day, none of this changes that fact that we are still using movement to help people address their pain and dysfunction, but it does allow us to ask better questions and come up with more effective treatments.